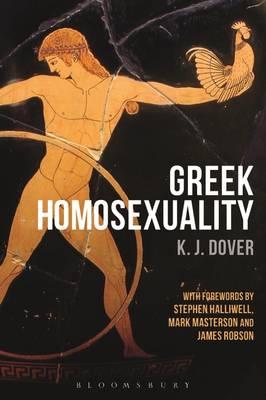

A lot of statements about the ancient Greeks, the Romans, and sexuality can be found on Christian websites. They give the impression that there’s complete certainty surrounding their comments, for example on the Greeks ‘tolerating homosexuality’, phrasing which implies a historically-consistent ‘thing’. But in fact there’s still plenty of debate in the scholarly community, where the statements that travel round the web originate. As part of the Day Job, earlier this week I attended the launch event for a re-issue of one of the most influential books from my student days: Sir Kenneth Dover’s Greek Homosexuality, first published in 1978. The cover of the re-issue, shown here, uses the same image as the original, Ganymede with a hoop (and a cock – yes – it’s a gift from Zeus), but zooms in on it; the hoop invites the viewer through to look at the boy’s genitals, but this new edition conveniently covers them with an ‘O’. That in itself is an interesting comment on what we can, and can’t, ‘see’ in the past.

In terms of whether the Greeks ‘had a word for it’, they had a lot of words for whichever ‘it’ we have in mind. For example, the meaning of the verb laikazein was unraveled only in 1980, when Harry Jocelyn published a scholarly discussion in Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society; in response, in the 1989 reprint of Greek Homosexuality, Dover duly corrected his earlier translation of ‘to have sexual intercourse’ to ‘to fellate’. That does seem to make a difference. But, back in 1978, Dover noted that there are no nouns in ancient Greek for either ‘heterosexuality’ or ‘homosexuality’,

since they assumed that (a) virtually everyone responds at different times both to homosexual and to heterosexual stimuli, and (b) virtually no male both penetrates other males and submits to penetration by other males at the same stage of his life.

As other scholars have shown, the English word ‘homosexuality’ only goes back to 1869.

Back in Athens

Dover distinguished between ‘episodic behavior at a superficial level’ (normal in ancient Athens) and ‘fundamental orientation of the personality’ (what we normally mean by ‘homosexual’ now). There’s an interesting actions/orientation division there which comes up in discussions today about what is and is not permitted for Church of England clergy. Dover’s book focused on the formalized Athenian system by which an older man would act as erastes to a young boy, his eromenos, a relationship where the man would woo the boy with gifts until he surrendered. When the boy started to develop facial hair, he would be cast aside, because the relationship was supposed to be a temporary one, with the boy going on to become an erastes in his own turn, and also to marry a woman. Dover compares this model of male behavior, including something that we would perhaps call ‘courtship’, to ‘heterosexual pursuit in British society in the nineteen-thirties’. Similar mixed messages could apply; an Athenian man would tell his fourteen-year-old son to avoid strange men on the street, but be content that his twenty-year-old son had ‘ “caught” the fourteen-year-old boy next door’.

To my mind, there’s an unfortunate effect of this being the aspect of Greek male sexuality which Christian sites tend to focus on: it leads to an elision between homosexuality and pederasty which is not appropriate today.

How far do you go?

Dover’s work has been characterized by David Halperin and other more recent scholars of ancient sexuality as ‘empirical’: he wasn’t interested in theory, but in working out the central facts from the evidence, much of it taken from images on Athenian vases showing erastes and eromenos, sometimes talking, sometimes kissing (as in the image from the Louvre shown here), sometimes with the older partner placing his penis between the younger man’s thighs, and with the younger man rarely showing any arousal. Other types of evidence, such as comedy, refer to anal intercourse, so was the relative modesty of the vase paintings really as far as it went? Did men avoid anal sex with other men? Was the older partner trying to protect his young friend (if that’s the right word) from some perceived shame of being the penetrated one, and thus the ‘female’ one? Or is it more that the viewer of these pots identified with the erastes, and wanted to see genitalia for himself? Perhaps the anticipation of intercourse was considered more exciting than seeing it happen. Were these ritualized courtship man-boy relationships the norm, or was it OK to have sex with boys of lesser social status in a purely physical encounter without all the courtship aspects?

In Classical Studies, there is still disagreement over whether this is all about penetration = power. Should we see the older man as ‘dominant’, or did the power really reside with the young boy who could – at least in the elite, courtship, model – refuse to allow the older man to do what he wanted? Further topics of debate include what the role of feelings was here; how ritualized was this behavior? Was it, in our terms, ‘romantic’? Also, was it ever OK to enjoy being the passive partner in anal sex? Was there was any concept of men who had sexual relationships with others of the same age (cutting through the age inequality of the standard pattern), throughout their lives (cutting through the limiting of sex with other men to specific stages of life)? Here’s one (controversial) view from James Davidson in Courtesans and Fishcakes (1997):

The Greeks did not award points for penetration. They did not see a gulf between a desire to penetrate and a desire to be penetrated and they certainly did not structure the whole of society let alone the entire world according to a coital schema. The whole theory is simply a projection of our own gender nightmares on to the screen of a very different culture.

Prehomosexuality

Another classicist, David Halperin, author of One Hundred Years of Homosexuality (1990), returned to the topic in 2000 and rejected any attempt to produce a single ‘history of homosexuality’. Instead, he distinguished four different forms of what he called ‘prehomosexuality’. One was effeminacy. Today, ‘we’ may interpret effeminacy as evidence of homosexuality; maybe one reason why Grayson Perry is so challenging is because alongside dressing as a woman – at one point, like Little Bo Peep – he’s a married, straight man with a daughter. In the ancient world, however, behavior coded as effeminate – such as spending a lot of time on one’s personal grooming – was seen as evidence of rather too much interest in … women. Women liked their men to be smooth-shaven and kempt.

Halperin’s second category was pederasty, characterized by one man being active and dominant, the other passive, as in Dover’s presentation of the erastes/eromenos relationship. The view of Victorian sexologists who called this ‘Greek love’ was that the dominant man ‘might not be sick but immoral, not perverted but merely perverse’. So long as this dominant man was not effeminate, and also had sex with women, there was no problem; as with effeminacy, his behavior could simply be evidence of his excessive sex drive. However, if he enjoyed the passive role in anal sex, this was quite another matter; real men shouldn’t do this. Halperin argued that the danger here is that sex becomes about hierarchy, about what one person ‘does to’ another. Mutuality is lost. Preferring the same sex or the other sex becomes like vegetarianism – a choice, not a deeply-held identity.

The third category was friendship, or ‘male love’. Here Halperin showed how the desire to read ‘homosexuality’ back into the past was responsible for recasting Achilles and Patroclus, or David and Jonathan, as ‘homosexual’. In these pairs, despite the claim to have found ‘another self’, one is dominant, the other the sidekick (and the sidekick usually dies). Again, hierarchy. But alongside this there existed a tradition of relationships between men which were equal, in which the two friends shared ‘a single mind, a single heart in two bodies’. This tradition, however, was deliberately separated from sexual expression, even though in modern ideas of homosexuality it forms part of the concept.

Halperin’s fourth category was inversion. In contrast to the other three categories, this one could not be read positively, but only negatively, because it involved the man being assimilated to the feminine rather than showing his valued, manly virtues through his relationships with other men. Where eromenoi surrender because of gifts – or threats – with their own desires remaining unaroused, the invert surrenders because of the desire to submit. Inversion is about gender more than sexuality; inverts want to be like women, and that’s wrong. Halperin argues that pederasty was a sexual preference without a sexual orientation – it was expected that the men involved would marry women – while inversion was an orientation without a sexuality, because its expression may not go beyond dress and demeanor.

Special pleading?

It’s always relevant to think about who is telling us something. Not surprisingly, I am more likely to believe something if I can see the evidence for myself (without apology, I identify with Doubting Thomas here). The evidence for ancient societies is complex, and reading it requires skills in using a range of types of source. It’s interesting that one reason why Dover’s book had an immediate effect was that he was a married and – from his controversial autobiography – enthusiastic heterosexual, unlike David Halperin or Michel Foucault. In 2012 Halperin published a book called How to be Gay – or, as less enthusiastic reviewers argued, how to form an identity as a gay white male in certain parts of America. But, as Halperin pointed out, nobody could accuse the heterosexual Dover of special pleading; he was also an Oxford Head of House, knighted in 1977 and eventually the President of the British Academy. As ever, being in the Establishment has an impact…

The moral and the natural

What all these writers have shown is that it’s impossible to take ‘sexuality’ as natural, as a given, and then trace ‘it’ through history. Categories develop, and shift. What we (and there are questions here about who ‘we’ are) include under the word ‘homosexuality’ may be entirely different from what was included even ten years ago. That applies to heterosexuality too; expectations shift. Interestingly, in a world where Christians sometimes deprecate the contemporary ‘obsession’ with expressing your sexuality, Halperin argues that it was Christianity – and specifically the confessional – which led to the identification of the self with the sexual self.

As we continue to project our gender nightmares on to the screen of history, a final word from Dover. He argued that a genital act was not in itself morally right or morally wrong, and what mattered was whether it was

welcome and agreeable to all the participants (whether they number one, two or more than two) … Any act may be committed in furtherance of a morally good or morally bad intention. Any act may have good or bad consequences.

Addendum: here’s an excellent blog post from Notches on why we want to create a ‘history’ and on the issues around assuming categories can be translated easily.

Hello! Would you allow me to translate the article to the portuguese and publish it in the R.Nott Magazine? Of course, all the credits will be given. It’s a great text.

LikeLike

I’d be very happy for you to do this! Could you send me a link or something when you’ve done it? Many thanks!

LikeLike

here it is, in our new issue! I hope you like it =)

http://www.rnottmagazine.com/#!Os-Gregos-não-tinham-uma-palavra-para-isso/c109z/575c74ce0cf2cc77abffc4f1

LikeLike

Very excited to be brought to an even bigger audience in Brazil – many thanks!

LikeLike

Thanks for this post! Still an important issue. Of course, if the Greeks, from our perspective, did not have a word for it, one could equally well say that from their perspective, *we* don’t have a word for it. Indeed I think this is quite evident from the problems we have in translating terms like ἐρώμενος or the biblical μαλακόi for that matter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Christof! The other term here is arsenokoitai, on which the jury still seems to be out (regardless of the ‘Oh it’s totally obvious!’ approach of some commentators). Do we have a word for that? Looks like Paul had to make one up…!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Greeks didn’t have a word for it [homosexuality] | ouartsmatters

Excellent article. Points up the human tendency to make history * say what we, as individuals and groups w/ respective agendas, WANT it to say. [* Ancient texts, too!]

LikeLike

Indeed – reading Evangelical Group in General Synod’s statement that “Some have suggested that faithful same sex relationships were not known in (pre) biblical times and therefore the bible is silent on this matter. This is not true: such relationships are acknowledged by Plato and others, and it is likely that Alexander the Great was in a same sex relationship with Hephaestion, as was Pausanius with poet Agathon.” makes me wonder how the complex sources for e.g. Pausanias/Agathon have so easily been reduced to a statement which sounds like these are two men who live down the road in 21st c Britain!

LikeLike

Pingback: Pausanias and Agathon: a ‘same sex relationship’? | sharedconversations

Interesting read. I’d suggest, though, that any person likely to be reading this article is almost certainly not included in the “we” of “we interpret effeminacy as evidence of homosexuality” — I’d have opted for “many people” instead.

Next I’m going to read the link in the addendum.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment – I’m sure you’re right! ‘We’ was meant in the sense of ‘Western society in general’, and ‘many people’ does express that better.

LikeLike

Pingback: Temple prostitution for Christians | sharedconversations

I’ve recently had my attention drawn to Richard Fellows’ post making some very valid points about NT Wright’s errors about Nero – again, showing a regrettable willingness to take all ancient Greek and Roman sources at the same level. The comments include a suggestion that Martial and Juvenal ‘record’ same-sex marriages – without any acknowledgement that their purpose in writing was hardly to ‘record’.

LikeLike

Pingback: Sexuality and the body: using ancient sources to support modern ideas

Pingback: Constantine the Great and the persecution of ‚androgynoi‘ – Männlich-weiblich-zwischen

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #50 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Os Gregos não tinham uma palavra para isso – R.Nott Magazine

Pingback: The Rise of Polyamory - Renew